Metal detecting holidays in England with the World's most successful metal detecting club.20 years plus.

Twinned with Midwest Historical Research Society USA.

|

|

Civil war, musket balls, powder measures and bayonet parts |

|

We find a large and diverse caliber range of musket balls being next to a major site of the English civil wars. I will be building a set of all the caliber's found with dates of these finds on this page.

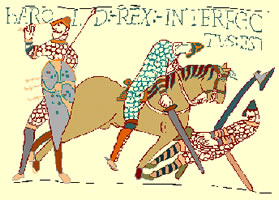

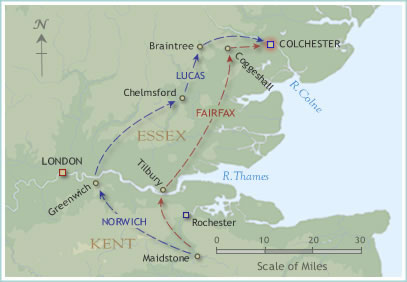

Siege of Colchester, Essex, 13 Jun-27 Aug 1648

Lucas deployed his forces to occupy the suburbs and bar the approach road from London into Colchester. Fairfax hoped to repeat his achievement at Maidstone and ordered an immediate attack. The Royalists resisted fiercely. Barkstead's infantry were thrown back three times, but the superior Parliamentarian horse overwhelmed the Royalists and the entire force was pushed back through the suburbs of Colchester towards the main town. Barkstead led the pursuit and advanced through the town gates only to be routed by a sudden cavalry charge and flank attack by Royalist infantry. Fairfax continued the assault until midnight, but was finally forced to abandon the attempt to carry Colchester by storm, having lost between 500 and 1,000 men. Colchester was strongly fortified. Fairfax resigned himself to committing his forces to a long siege despite the threat from the Scots and Langdale's Royalists in the north of England. Roads leading to Colchester were secured against the possibility of the Royalists breaking out and Parliamentarian warships blockaded the mouth of the River Colne to prevent supplies being shipped in. All through June, the Parliamentarians worked on constructing a ring of forts around the perimeter of the town where siege guns were mounted to batter the walls. On 2 July the circumvallation of Colchester was completed. On 14 July Fairfax's troops seized the Hythe, Colchester's harbour on the Colne. The following day the gatehouse of the old abbey which commanded the southern wall of the town was taken. The siege grew bitter and brutal. Uncharacteristically, Fairfax's troops committed a number of atrocities, including the desecration of graves in the Lucas family vault and the torturing of a messenger boy. The civilians of Colchester were mostly Parliamentarian sympathisers but Fairfax refused to make any concessions to alleviate their suffering. On the other side, the Royalists were accused of using poisoned bullets, i.e. bullets roughened and then rolled in sand to increase the likelihood of causing gangrenous wounds. By the beginning of August, provisions in Colchester had almost run out and the defenders were starving. Lord Norwich and Sir Charles Lucas clung on with the sole intention of keeping a large contingent of the New Model Army pinned down at Colchester but on 24 August, news came of the defeat of Langdale and the Scots at the battle of Preston. Realising that their cause was lost, the Colchester Royalists began negotiations for surrender. Colchester siege diary [offsite] The Royalist Martyrs Colonel Farre managed to escape and Sir Bernard Gascoigne was reprieved because he was a foreign national, but the execution of Lucas and Lisle went ahead. Fairfax's decision — almost certainly influenced by Commissary-General Ireton — was controversial. Although the Royalist officers had surrendered on mercy, it was unprecedented in the civil wars for an execution to be carried out under such circumstances. Ireton and Fairfax justified the severity of the sentence on the grounds that Lucas and Lisle had caused unnecessary bloodshed by attempting to defend an untenable position. Furthermore, Lucas had broken his parole by going to war against Parliament a second time, and was himself accused of executing prisoners in cold blood during the siege. The executions reflect the sense of anger and frustration felt by Parliamentarians at the Royalists who had inflicted a second civil war upon the nation. They were calculated to deter others from taking up arms against Parliament and to set a precedent for the execution of Parliament's enemies. The executions of Lucas and Lisle were carried out in the evening of 28 August 1648 in Colchester Castle. They died courageously and were swiftly elevated to the status of Royalist martyrs. Pamphlets appeared within days condemning their barbarous murder by Fairfax. According to legend, the grass never again grew on the spot where they were killed. The area is now paved over and marked by a memorial obelisk.

Great eyeball find 17/18thC Musket flint

Musket and shot finds - examples 22.92g, 0.31 inch - 18thC French 40.51g, 0.776 inch 17thC English 31.02g, 0.697 inch 18thC English

Musket balls

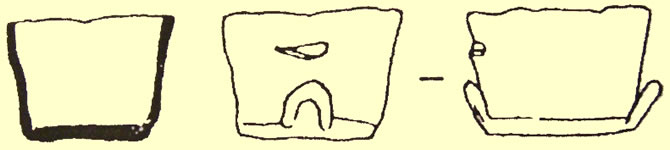

Mold seam - a thin line around the circumference of the musket ball. Casting Sprue - a small

raised cylinder from the lead inlet channel in the mold. This i.e. The difference between the ball and the caliber is known as windage. Typically the windage is approximately 0.05- 0.10mm. An example is a military British Brown Bess has a bore of 0.75 inches or 75 caliber, but would take a 0,693 inch diameter musket ball. A 69 caliber French Charleyville musket usually took a 0.63 inch ball. However, during the 17th/18thC musket balls were categorized not by diameter but as to how many musket balls would weigh a pound. For example a service British brown Bess musket took musket balls that were 29 per two pounds.

18thC Brown Bess - 0.685 inch, 75 Caliber 31.55g The weapons

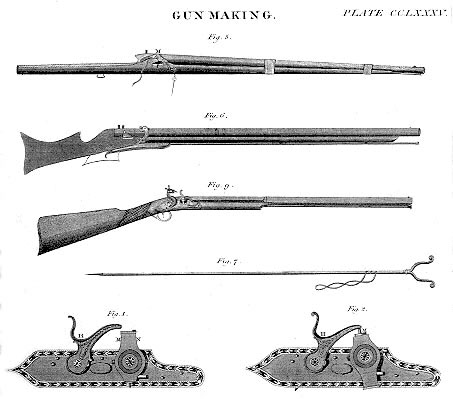

The smoothbore musket was a long-ranged firearm derived from the earlier arquebus (or hackbutt) during the 16th century. The musket was initially heavier than the arquebus, requiring a wooden rest to aim, and had a length of 6 ft compared to the arquebus's 4 ft. Calibers of the weapons varied from 0.50 inch to 0.75 inch. The musket also had a longer range and higher muzzle velocity than the arquebus. The arquebus was preferred by some, because of its easier handling (skirmishers preferred the arquebus) and faster rate of reload (2 or more minutes for the musket versus 1 to 2 minutes for the arquebus). The heavier musket also absorbed more of the recoil at discharge. However, the lower muzzle velocity of the arquebus did not always penetrate armor, which was still worn by pikemen and cavalry. In the Spanish and Imperialist armies, there were bodies of both arquebusiers and musketeers. The bayonet was not invented yet. Arquebusiers and musketeers depended on bodies of pikemen to defend themselves from cavalry charges. The musketeers and arquebusiers also carried swords for fighting hand-to-hand. However, their firearms were usually used as clubs in melees. Both weapons used a matchlock to fire the weapon and were muzzle loaded. To load the weapon, the shooter would unplug a wooden container called an apostle (because there were 12 of them) from his leather bandoleer. He would then pour a pre-measured amount of loose gunpowder from the apostle into the muzzle of the barrel. Then a lead ball from a sack was placed into the muzzle and rammed home into the chamber with a wooden scouring stick (a.k.a. ramrod). The powder pan on the side of the musket barrel was opened and loose gunpowder from a powder flask was poured into it. A glowing match made from cord soaked in saltpeter was placed in the hammer of the lock. The shooter would aim his weapon. The trigger was pulled forcing the match into the pan igniting the powder. The flash from the pan would travel into the chamber through a hole and ignite the powder. The expansion of gases would force the ball on its way to the intended target. The powder in the chamber ignited slowly. Too much powder resulted in the ball leaving the muzzle before all of the powder had been ignited. A correct balance between charge size and length of barrel was important to ensure that all of the powder was ignited before the ball left the muzzle of the barrel. The correct relationship between charge size and barrel length maximizes the muzzle velocity of the ball. In general a higher muzzle velocity results in greater range and accuracy, and better penetration into armor. Reloading took a long time, involving some 48 distinct movements. Elaborate methods were designed to provide a continuous stream of fire. Troops were deployed in formations of 6 or more ranks to deliver their shots one rank at a time. After one rank of shooters fired a newly reloaded rank would move in front of the them (fire by introduction) or the recent shooters would move to the rear and reload (fire by extroduction), exposing a loaded rank. During the late 16th and early 17th centuries many Protestant armies experimented with lighter muskets that were easier to handle and load. This decreased the reload times down to 2 or less minutes. In some cases the musketeer did not need a musket rest. The arquebus was dropped in favor of the lighter muskets. The lighter muskets still had good armor penetration power. This and the increasing effectiveness of light artillery caused armor usage to diminish. The Protestant armies, armed with their lighter muskets, experimented with salvo fire. This involved the fire of two or more ranks simultaneously. The Huguenots of France under Henry of Navarre first used this method during the French Religious Wars. The Dutch in their war of independence also used this method against the Spanish. Finally the Swedes under Gustavus Adolphus used salvo fire very effectively. A Swedes brigade is reported to have stopped seven Imperialist cavalry charges with salvo fire at the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631) during the Thirty Years' War. Another major contribution by the Swedes was the adoption of the paper cartridge. A musketeer was equipped with a cartridge box that contained pre-made rounds of powder and ball. The musketeer would grab a cartridge from the box, then bite down on the ball and tear the cartridge open. He would pinch off a small amount of powder in the cartridge and pour the remainder into the muzzle of his musket. The remaining powder was placed into the pan. The ball was retrieved from his teeth and placed into the muzzle. Then he rammed the ball down the barrel until it was well seated into the chamber. The musketeer then fired his weapon as before. The Swedish combination of lighter, handier muskets, with paper cartridges, and salvo tactics enabled the Swedes to reload at one-minute intervals. Flintlocks

17th C lead gunpowder measure. Cap for the powder horn and measure for the gunpowder

|

18thC musket ramrod guides

18thC bayonet frogs

Musket plate ? SGT Huggons York Musket parts

Sword and dagger page

|

Musket

balls are manufactured by pouring molten lead or another alloy into a

two part single or a multiple cavity mould.The casting sprue is cut close

to the ball and any flashing around the mold seam is removed.

Musket

balls are manufactured by pouring molten lead or another alloy into a

two part single or a multiple cavity mould.The casting sprue is cut close

to the ball and any flashing around the mold seam is removed. is usually clipped off close to the surface of the ball, If you excavate

a musket ball that is round, has a mold seam and a casting sprue then

it was probably dropped and not fired. However not all dropped musket

balls have a mold seam or casting sprue. Transportation methods can erase

this line by rubbing together in transit. When the diameter is measured

this can be used to determine the caliber.

is usually clipped off close to the surface of the ball, If you excavate

a musket ball that is round, has a mold seam and a casting sprue then

it was probably dropped and not fired. However not all dropped musket

balls have a mold seam or casting sprue. Transportation methods can erase

this line by rubbing together in transit. When the diameter is measured

this can be used to determine the caliber.

In

the late 16th century, the firelock was invented. This invention eliminated

the glowing match and replaced the match mechanism with a flint. The flint

struck against steel over the pan, emitting sparks. The flintlock decreased

the reload time, but was more expensive than the matchlock mechanism.

The abundance of gunpowder in the artillery train prohibited the use of

burning objects (glowing match) in the vicinity and the firelock became

the preferred weapon for the artillery train guards. The firelock was

also known as a fusil, and this is the origin of the term fusilier. Flintlocks

became more popular over time as the cost diminished and reliability improved.

During the Malburian wars of the early 18th century, the matchlock was

completely replaced by the flintlock. Another advantage of flintlocks

over firelocks is formation. Matchlocks require more distance between

individuals because of the glowing match and the necessity of moving ranks

after each salvo, whereas the flintlock allows a close ordered formation.

In

the late 16th century, the firelock was invented. This invention eliminated

the glowing match and replaced the match mechanism with a flint. The flint

struck against steel over the pan, emitting sparks. The flintlock decreased

the reload time, but was more expensive than the matchlock mechanism.

The abundance of gunpowder in the artillery train prohibited the use of

burning objects (glowing match) in the vicinity and the firelock became

the preferred weapon for the artillery train guards. The firelock was

also known as a fusil, and this is the origin of the term fusilier. Flintlocks

became more popular over time as the cost diminished and reliability improved.

During the Malburian wars of the early 18th century, the matchlock was

completely replaced by the flintlock. Another advantage of flintlocks

over firelocks is formation. Matchlocks require more distance between

individuals because of the glowing match and the necessity of moving ranks

after each salvo, whereas the flintlock allows a close ordered formation.