Metal detecting holidays in England with the World's most successful metal detecting club.20 years plus.

Twinned with Midwest Historical Research Society USA.

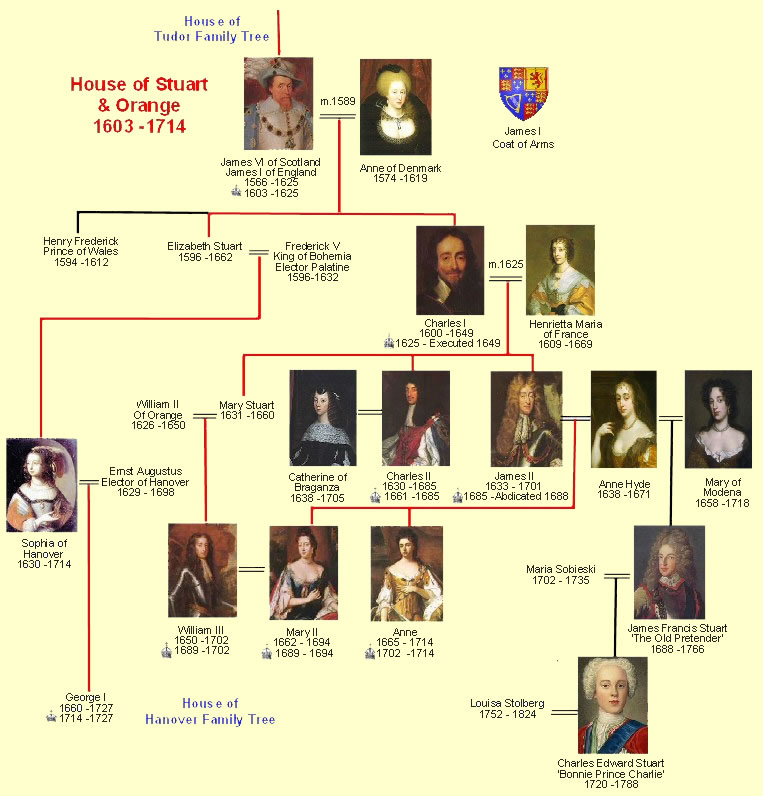

House of Stuart, 1603-1714

The Stuarts were the first kings of the United Kingdom. King James I of England who began the period was also King James VI of Scotland, thus combining the two thrones for the first time. The Stuart dynasty reigned in England and Scotland from 1603 to 1714, a period which saw a flourishing Court culture but also much upheaval and instability, of plague, fire and war. The end of the Stuart line with the death of Queen Anne led to the drawing up of the Act of Settlement in 1701, which provided that only Protestants could hold the throne.

Stuart timeline

|