Saxon

and Roman gold

Archaeology

South-East

CONTENTS

1.0 INTRODUCTION

2.0 SITE TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY

3.0 ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND

4.0 CARTOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE

5.0 AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHS

6.0 WALKOVER SURVEY

7.0 EXISTING IMPACTS ON ARCHAEOLOGICAL POTENTIAL

8.0 SUMMARY OF POTENTIAL AND CONCLUSION

9.0 PRELIMINARY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE WORK

10.0 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SOURCES CONSULTED

Appendix 1: Summary Table of SMR Entries

Appendix 2: Tithe Apportionment (1839)

Appendix 3: Tithe Apportionment (1844)

LIST

OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Fig. 1 Site Location and SMR data

Fig. 2 1777, Chapman & Andre

Fig. 3 1796-1800, Ordnance Survey Draft Drawings, 1-inch Old Series

Fig. 4 1839/1844, Tithe Maps (composite)

Fig. 5 1875, Ordnance Survey 6-inch, 1st ed., Sheet XXVIII.

Fig. 6 Detailed Cropmark Plot of Site

Fig. 7 Cropmark Plot showing wider landscape PLATES

Plate 1. Aerial Photograph (22/06/1980) – view of western field

looking NW

Plate 2. Aerial Photograph (03/07/1986) – view of site looking

NW

Plate 3 Aerial Photograph (22/06/1976) – view of site looking

SE

Plate 4 Aerial Photograph (17/07/1980) – view of cropmarks south

looking NW

Archaeology

South-East

East of Essex

1.0

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Archaeology South-East (a division of the University College London

Field Archaeology Unit) has been commissioned by to carry out an archaeological

appraisal, consisting of a desk based assessment and preliminary walkover

survey, of farmland to the East of Colchester, Essex (Fig. 1).

1.2 This report follows the recommendations set out by the Institute

of Field Archaeologists in Standards and Guidance for Archaeological

Desk-Based Assessments and utilises existing information in order

to establish as far as possible the archaeological potential of the

site.

1.3 This report has been prepared using a standard set of sources

comprising archaeological, photographic and cartographic data, including

appropriate published works. During initial discussions between the

author and the client, and during a subsequent site visit, attention

was drawn to a vast array of artefactual material that has been recovered

through the use of metal-detectors over a number of years by the client

and his associates. The results of this work are far too numerous

to deal with in any detail in a report of this scope, and are, in

any case, catalogued in impressive detail on two websites, one run

by the client (www.colchestertreasurehunting.co.uk) and the other

relating to the Celtic Coin Index, maintained by Philip de Jersey

of the Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford (www.writer2001.com/cciwriter2001/).

It is the intention of this report,

therefore, to deal with these finds in a summary form and to concentrate

on those aspects of the development of the site that are less familiar,

particularly the important cropmark evidence. It is to be hoped that

the coin evidence will be the subject of a detailed study in the future.

1.4 The site location, and study area is shown on Fig. 1. Centred

on National Grid

Reference XXXXX , the site lies approximately XXXX metres to the East

if XXXXXXXXThe site occupies the south-western half of a broadly square

plot of land occupied by two arable fields, and measuring approximately

23 hectares. The site is enclosed by a combination of hedgerows of

18th-19th century date and modern fence lines, and the present land-use

is arable, which at the time of the site visit had been harvested

1.5 It should be noted that this form of non-intrusive appraisal cannot

be seen to be a definitive statement on the presence or absence of

archaeological remains within any area but rather as an indicator

of the area’s potential based on existing information. Further

non-intrusive and intrusive investigations such as geophysical surveys

and machine-excavated trial trenching are usually needed to conclusively

define the presence/absence, character and quality of any archaeological

remains in a given area.

1.6 In drawing up this desk based assessment, cartographic and documentary

sources held by the Essex County Records Office at both Chelmsford

and Colchester have been consulted. Archaeological data was obtained

from the Sites and Monuments Record held by Essex County Council.

Relevant sources held withinChelmsford and Colchester reference libraries

and the Archaeology South-Eastlibrary were utilised, and appropriate

Internet databases interrogated. These included: The Defence of Britain

Project, The English Heritage NMR Excavation

Index and National Inventory, and the Magic website, which holds government

digital data of designated area sites in GIS map form. Relevant aerial

photographs from the National Monuments Record, Swindon, have also

been also obtained.

Anglo

Saxon strap end

2.0

SITE TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY

2.1 The area has no specific topographical features other than being

generally flat and level, with a gentle slope down to the stream valley

along the southern and south-western margin of the site.

2.2 The natural geology of the site comprises sands and gravels of

the Kesgrove Formation, with London Clay along the southern margin.

3.0

ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND AND POTENTIAL

3.1 Introduction

3.1.1 The Sites and Monuments Record maintained by Essex County Council

(ECC),and held at County Hall, Chelmsford was consulted. Details were

taken of all archaeological sites and listed buildings within a 1-kilometre

radius of the site (hereafter referred to as the Study Area). Sites

with generalised grid references within the 1-kilometre radius were

also included. The identified sites are tabulated in Appendix 1 and

shown plotted on Fig. 1 (site numbers within brackets refer to cropmarks).

3.2 Scheduled Ancient Monuments and Designated Sites

3.2.1 These comprise cultural heritage sites of a higher degree of

status and significance, some of which enjoy a certain degree of legal

protection from development and include Scheduled Ancient Monuments

(SAMs), Listed

Buildings, Historic Parks and Gardens, Ancient Woodland and Conservation

Areas. These designations and others such as Archaeologically Sensitive

Areas and Areas of High Archaeological Potential are typically detailed

in BoroughCouncil Local Plans and County Council Plans with appropriate

planning policies

pertaining to each category.

3.2.2 No designated sites lie within the study area, although two

Listed Buildings are present in the vicinity

3.3 Archaeological Periods Represented

3.3.1 The timescale of the archaeological periods referred to in this

report is shown below. The periods are given their usual titles. It

should be noted that for most cultural purposes the boundaries between

them are not sharply distinguished, even where definite dates based

on historical events are used. Sub-divisions within periods are not

considered separately.

Prehistoric: Palaeolithic (c. 500,000 BC - c. 10,000 BC)

Prehistoric: Mesolithic (c. 10,000 BC - c.5,000 BC)

Prehistoric: Neolithic (c. 5,000 BC - c.2,300 BC)

Prehistoric: Bronze Age (c. 2,300 BC - c. 600 BC)

Prehistoric: Iron Age (c. 600 BC - AD 43)

Romano-British (AD 43 - c. AD 410)

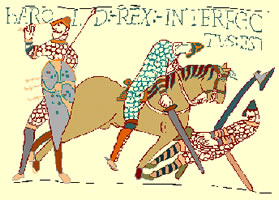

Anglo-Saxon (c. AD 410 - AD 1066)

Medieval (AD 1066 - AD 1485)

Post-medieval (AD 1486 to date)

3.4 Prehistoric: Palaeolithic

3.4.1 Palaeolithic material has been found at a number of sites in

Essex and the neighbouring part of Suffolk, with significant quantities

of material derived from the river valleys around both Colchester

and Ipswich. As with elsewhere in Britain the vast majority of these

find spots are of artefacts, typically hand axes, which have almost

certainly been washed into river terrace deposits at various times

throughout the Middle and Late Pleistocene (Wymer 1980). Importantly

however, flint tools have been recovered from a surviving occupation

surface at

Clacton-on-Sea, south-east of the study area. Whilst the majority

of archaeological data relating to this period relates to isolated

artefactual recovery, it is possible that significant in situ sites

remain to be discovered, as Essex was situated on the fringe of the

great Anglian ice sheet some 450,000 years before present, a period

immediately post-dating the earliest known colonisation of Britain

(Pitts and Roberts 1997).

3.4.2 The Essex SMR records show no Palaeolithic finds within the

Study Area.

3.5 Prehistoric: Mesolithic

3.5.1 The Mesolithic saw the return of human communities to Britain

in response to improving post-glacial climatic conditions. The warming

climate led to the spread of woodland that provided a rich source

of resources for human groups. Settlements comprised semi-permanent

base camps occupied during the winter months and a series of seasonal

hunting camps. Evidence for this period from much of Essex, particularly

in situ material, is rare, consisting predominantly of diagnostic

lithics, such as microliths and transversely sharpened core-adzes,

forming flint scatters. The area between the Rivers Stour and Colne

has a relatively high density of Mesolithic finds and this may indicate

ongoing exploitation by transient groups of people, rather than by

sedentary communities

settling in the area. The area formerly contained a concentration

of heathlands used as common pasture (Hunter 1999), and similar areas

have been identified in other counties as being favoured zones for

Mesolithic occupation, possibly through the drier, less dense woodland

proving easier to traverse.

3.5.2 The Essex SMR records one Mesolithic find within the Study Area.

This comprises a flint tranchet axe and probably represents a casual

loss by a mobile hunting community.

3.6 Prehistoric: Neolithic

3.6.1 The Neolithic saw the development of agriculture and the first

evidence for largescalecommunal activity. New ideas relating to the

domestication of animals and the cultivation of cereals were adopted,

together with new technologies such as pottery. Environmental evidence

indicates a major phase of woodland clearance

taking place, as land was opened up to provide fields and sacred spaces.

Essex is replete with Neolithic sites, both domestic and monumental.

Domestic sites are often represented archaeologically by concentrated

flint scatters with associated pits, and occasionally ditched enclosures,

whilst standing earthworks, such as

causewayed enclosures, earthen long and round barrows, cursus monuments,

henges and standing stones are indicative of the ritual environment.

The area between the Rivers Stour and Colne is no exception, with

a number of important sites, such as at Lawford . Many of these sites

are represented by cropmarks (see Section 5).

3.6.2 The Essex SMR records two finds of Neolithic date within the

Study Area. Both comprise isolated flint artefacts, an axe head and

a chisel .

3.7 Prehistoric: Bronze Age

2000BC

Bronze Age flat axe

3.7.1 The Bronze Age is best characterised by the introduction of

metals, firstly gold and copper and later bronze, and first developed

as part of a cultural package labelled as Beaker.1The transition to

the Bronze Age in terms of the landscape is marked by a significant

increase in both visible settlement patterns, and in the

number of round barrows constructed, often with single inhumation

or cremation burials. These monuments heralded a new way of thinking

about society as they represented the burial of individuals in contrast

to the communal burials of the 1 It used to be thought that the Beaker

assemblages, which often included archery equipment, wereintroduced

by a group of invaders, the ‘Beaker folk’. This idea has

been replaced by one of indigenous native people adopting a new ‘lifestyle

package’, with no associated movement of populations preceding

Neolithic. This suggests the emergence of social elites, the division

of people into the rulers and the ruled. Although in many parts of

the country (e.g. the South Downs) the barrows remain as upstanding

earthworks, in the eastern counties they tend to have been ploughed

away, leaving only ring ditches and

cropmarks. By the Middle Bronze Age, c.1500 BC, nucleated cremation

cemeteries predominated within an increasingly structured world, and

agricultural demarcation of the landscape assumed greater visibility

in the landscape through the development of field systems.

850BC

Bronze Age axe hoard

3.7.2 The Essex SMR records two Bronze Age sites within the Study

Area. Both are artefactual in nature. The most significant comprised

a cremation urn (a tripartite collared urn) of Early Bronze Age date,

in the field just southwest of the Site. The urn was found to contain

‘six pints’ of bones, identified as those of two individuals,

an adult and a child. The find undoubtedly forms part of a much wider

ritual landscape represented in the

extensive cropmark evidence that is known in the vicinity (see Section

5). The second SMR entry relates to a casual find of a Late Bronze

Age socketed axe head . No evidence was found of Beaker period activity

to substantiate a local tradition of a Beaker burial located in the

vicinity. It is probable that this is a confused reference to the

Bronze Age cremation discussed above.

3.8 Prehistoric: Iron Age

3.8.1 The Early and Middle Iron Age (up to c.100BC) saw the continuation

of trends developed in the Late Bronze Age. In the Late Iron Age most

of Essex and Suffolk were in the territory of the Trinovantes, whose

tribal capital was at Camulodunum (Colchester), an open site bounded

by long stretches of ditches and banks. It is known that the situation

was not static as, for example, the Trinovantes’ capital was

attacked and occupied by the Catuvellauni (from the west) under Tasciovanus

c.20 BC, although Trinovantian rule returned under Dubnovellaunus

(de Jersey 1996). The Trinovantes were subsequently absorbed into

the Catuvellaunian empire under Cunobelinus.

Celtic

gold coins from 45BC

3.8.2 Two main groups of evidence exist for Iron Age activity in the

vicinity of XXXX. One comprises the linear cropmarks of field systems,

ditched trackways and enclosures (see Section 5 for details). The

other consists of a considerable number of Iron Age coins, including

a significant and unusual proportion of gold

issues ( pers. comm. – see Website for details). The political

ebb-andflow outlined above (see 3.8.1) is reflected in the variety

of different tribal groupings represented in the coin finds, which

exist as both single finds and as

hoards, with an interesting concentration around XXXX. The prevalence

of gold coinage in this area must be associated with the proximity

of Camulodunum. It is also possible that peninsula was afforded some

special status. However, it would be unwise to speculate too far at

this point, given that many of the artefacts are literally ‘fresh’

out of the ground and have not had time to be thoroughly ‘digested’

by the relevant experts, and also by the fact that the outstanding

results from this area may be skewed by the unusually sustained and

systematic attention it has received over a number of years.

3.8.3 Ironically, given the number of coins and other artefacts found

over recent years, the Essex SMR records no Iron Age sites within

the Study Area itself.

Roman

finds

3.9. Romano-British

3.9.1 Roman settlement in Essex comprised a network of small towns

surrounded by a dense scatter of smaller settlements, including villas

but mainly consisting of individual farmsteads. The exception to this

pattern comprised the native centre of Camulodunum, captured by Roman

troops (with the aid of an elephant) in

AD43 and established first as a fortress and subsequently as the provincial

capital. Destruction during the Boudican uprising saw a reduction

in status to provincial backwater. In landscape terms, there was much

continuity with earlier periods, although there was a gradual transformation

in building types, with circular round houses replaced by rectangular

structures of stone and timber construction. Villas were established

in the countryside, surrounded by extensive field systems, many of

which are still visible as cropmarks (see Section 5).

3.9.2 The Essex SMR records one Roman-British area. This comprises

a gold coin of Drusus Senior (brother of the Emperor Tiberius) found

on a farm in c.1890

Offa

Rex Saxon coin

3.10 Anglo-Saxon

3.10.1

Essex was one of the first areas to be heavily settled by Germanic

peoples, who tended to prefer the more tractable soils of the coastal

plan and river valleys. A unified kingdom of the East Saxons emerged

by the late 6th century from a patchwork of smaller territories possibly

based on late Roman precursors (Rippon

1996). The kingdom lasted until the 9th century, when it was subsumed

into Wessex. Little is known of this Anglo-Saxon area , although the

name would suggest it originated as a daughter settlement of XXXXX

. The two parishes appear to form sub-divisions of a much larger original

estate. The name is of Saxon origin , but the earliest reference is

in the Domesday Book in 1087. The settlement pattern, which largely

developed from the Mid-Late Saxon period, differed from the classic

Midland pattern of nucleated villages clustered around church and

manor and surrounded by open fields. Essex conforms to the ‘Ancient

Countryside’ pattern (Rackham 1980; Roberts & Wrathmell 2000)

of dispersed settlement comprising small hamlets and isolated farmsteads

set within a mosaic of irregular enclosures and patches of open field

arable cultivation. Isolated churches are not indicative of former

nucleated settlement sites (Deserted Medieval Villages) but are rather

a central focus to which a scattered population would gather for significant

social events (attending church, festivals, markets etc).

3.10.2 The Essex SMR records reveal no Anglo-Saxon sites within the

Study Area, although a number of artefacts have been recovered during

metal-detecting sweeps.

3.11 Medieval

3.11.1 This area developed as part of a dispersed settlement, and

are listed together in Domesday (Reaney 1969). The parish appears

to have been divided among three manors both prior to the Conquest

and subsequently. The early historian Philip Morant identified the

area occupied by Queen Edith (wife of Edward the Confessor) in 1066,

which was subsequently granted to Walter the Deacon (Morant 1768)

and held by an unnamed knight. The record shows a mixed farming economy,

with plough teams indicating some arable cultivation and the presence

of cattle, horses and 100 sheep indicating extensive pasture. Woodland

is listed as suitable to support 40 pigs, although this is a unit

of measure rather than of stock (the record specifies 12 pigs later

in the entry), and the woodland itself may not necessarily have been

close by – many manors had out lying pannage rights (the right

to feed pigs in the manorial woodland) in areas of common waste beyond

the bounds of the manor itself. By the 12th century, the manor formed

part of the Barony of Hastings, held by the Hastings family of Little

Easton near Great Dunmow. The 14th century saw the manor in the hands

of the Godmanston family, two members of which (Walter in 13812 and

John in 1452) served as Sheriff of Essex and Hertfordshire.

3.11.2 The church of was the focal point of the parish, indicated

by its position at the hub of a network of roads, tracks and paths

that stretch out to every corner of the parish. It is not mentioned

in Domesday (which is not, however, proof that it did not exist),

but the earliest part of the existing structure is the early 12th

century nave .

3.11.3 The Essex SMR records three medieval sites within the Study

Area. , while the remaining two entries relate to artefacts found

within the churchyard

3.12 Post-medieval

3.12.1 The post-medieval period, prior to the 18th century, had seen

a gradual modification of the Medieval and earlier landscape, much

of which had become enclosed in piecemeal fashion. Up until the 18th

century, the general field patterns were

probably consistent with the irregular and sinuous enclosure of medieval

date, representing original assarting from the woodland, of which

only a small portion survives in the narrow sinuous plot across the

road. These early enclosures elsewhere were modified during the 18th

century to

produce large regular fields with straight boundary hedges of hawthorn.

Most of these later boundaries have been removed since 1950. The history

of the site during this period has been one of uneventful agriculture.

3.12.2 The Essex SMR records no post-medieval sites within the Study

Area.

3.13 Undated

3.13.1 The Essex SMR records eight undated sites. One entry is of

little significance, relating to an undated wooden pipe found in a

pond. The remaining seven entries are crop marks, which will be discussed

in greater detail in Section 5 comprises field boundaries and a ring

ditch, XXX comprises at least 25 ring ditches and a series of linear

features, XXX (including the Site) consists of mainly linear features

suggestive of field systems and trackways, but also includes numerous

ring ditches and several enclosures.XXX consist of field boundaries,

XXXX comprises ring ditches, pits and two trackways. Finally, XXX

is made up of pits and linear features. Dating crop marks is notoriously

difficult, and some may suggest the presence of prehistoric, or later

archaeological features

(see Section 5 for further discussion).

4.0

CARTOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE

4.1 The earliest map consulted of sufficient detail was Chapman and

Andre’s survey of Essex from 17773 (Fig. 2). This clearly shows

the site in a recognisable form, with the sinuous and maze-like medieval

road network. The existence at this time of unenclosed heathland commons,

utilised as common waste by the surrounding communities, is clear

from the map, with examples at Ardley Heath and Shuckmore Heath. The

land use of the site itself cannot be discerned, but is likely to

have been open farmland.

4.2 The Ordnance Surveyors’ draft plan of 1796-1800 (Fig. 3)

shows the area with more detail added. The field patterns shown bear

little resemblance to those of the 19th and 20th centuries, although

enough points of agreement can be discerned to indicate that the field

patterns shown were a fairly accurate record rather than a

stylistic convention. The pattern shown on the map suggests that they

represent the original medieval piecemeal enclosure landscape before

it was reorganised to form the regular geometric pattern visible on

later maps. The reorganisation must have taken place only a few years

after this map was surveyed.

3 An earlier map of the area dating to 1627 was listed in the Essex

Record Office in Chelmsford, but could

not be found

4.3

The Tithe Maps for the parishes (1844) (Fig. 4) show a different landscape

to that depicted in 1800. The original field patterns had been completely

swept away, to be replaced by large rectangular fields forming a regular

grid pattern with straight boundaries. This pattern is fairly piecemeal

in nature, as the maps indicate other blocks of fields in the vicinity

that have retained the original medieval patterns. This may perhaps

reflect a wealthier or more progressive landowner willing to spend

money reorganising his land to accommodate new farming techniques

while his neighbours were unwilling or unable to follow suit. Field

names on Tithe Maps

can often indicate sites of archaeological potential. In this case,

they are of little interest, although the name Cock Field may refer

to a former use for cockfighting. Osier Meadow indicates the streamside

cultivation of willow to provide withies for basket making, etc (Field

1993).

4.4 The 1st edition 6” Ordnance Survey map of 1875 (Fig. 5) shows

that more modifications had taken place during the previous thirty

years, with the site now covered by three huge fields with several

smaller plots along the southern and eastern margins. The 1897 and

1923 editions of the 25” map (not illustrated) show

an identical picture, and the current field pattern is very similar

apart from the removal of several of the smaller field boundaries

around the edge.

Roman

finds

5.0 AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHS

5.1 A search was made of the vertical and oblique collections of the

National Library of Air Photographs held at the National Monuments

Record Centre, Swindon. A total of 15 vertical prints and 67 specialist

oblique laser prints were consulted spanning the period 1946-1996.

Only five of the examined photographs had no cropmarks visible (marked

with an * in the tables). Crop mark plots were also obtained from

Essex County Council SMR office (see Figs 6 & 7). The following

aerial photographs were checked.

Table 1: Vertical Aerial Photographs

Sortie No. Frames Date Scale XXX

5.5

The ring-ditches are the earliest type of cropmark to be identified,

generally of Early-Middle Bronze Age date, although some may extend

back into the late Neolithic. A number of particularly large circular

cropmarks, up to 30m in diameter and comprising wide encircling ditches,

have until very recently been interpreted as henges (circular ritual

sites of Late Neolithic date), of which one example, described as

a Class 2 henge (i.e. having two opposing gaps or ‘entrances’

in the encircling ditch), is visible within the western part of the

site (Feature L on Fig. 6) (Erith 1968; Hedges 1980; Holgate 1996;

Kemble 2001). However, recent excavations on similar sites within

the county have consistently reinterpreted them as either Late Bronze

Age enclosures or Medieval and later windmills (Brown & Germany

2002).

5.6 Linear cropmarks forming enclosures Extensive areas of cropmarks

forming rectilinear enclosures are a major feature in the landscape

(as revealed by air photographs), often consisting of complex systems

suggesting superimposed multi-period landscapes. Some are likely to

be of prehistoric origin – at many sites, the rectilinear enclosure

boundaries respect the positions of ring-ditches, suggesting that

the barrow cemeteries were still

visible in the landscape as upstanding earthworks. Some may even be

contemporary with the cemeteries, representing a ritual focus set

within field systems – such an arrangement is represented at

Ardleigh.

5.7 However, many of the enclosures may well be of later date, primarily

Iron Age and Romano-British, and lie within a much larger system of

cropmarks aligned on common NW-SE and SW-NE axes which pre-empt a

similar alignment in the medieval and later field boundaries and road

network. The lack of any significant correlation between the cropmarks

and the medieval field boundaries (as indicated on the 1800 map) suggests

that medieval enclosures may have been laid out afresh following a

period of abandonment (perhaps associated with

woodland regeneration, as hinted in Domesday), but within a landscape

whose basic ‘grain’ was still evident (probably in the form

of trackways now followed by modern roads and footpaths).

5.8 Other linear cropmarks

These are difficult to interpret and date, representing both isolated

linear boundary features identifying the edges of discrete areas,

whether individual fields or larger territorial units such as estates,

and also constituent parts of

enclosures/field systems, of which the other elements have been destroyed

(or are not visible as cropmarks). They range in date from the Neolithic

up to the 20th century.

5.9 Sinuous cropmarks

These cropmarks are clearly differentiated from the examples discussed

above by their sinuous nature. They wind through the landscape with

little or no clear relationship with the other types of cropmark,

and are often wider with more diffuse edges. These are probably of

natural origin, representing geological features or the course of

former waterways (palaeo-channels). It is known from environmental

studies that the flat plateau that now characterises the north Essex

landscape was formerly dissected by many more small stream valleys

than are

now evident in the modern landscape. These valleys have subsequently

silted up.

5.10 Small discrete cropmarks

These cropmarks are also difficult to characterise and date. Some

may represent geological features of natural origin, while others

may be archaeological in nature, perhaps representing clusters of

pit graves.

5.11 The andscape

The Site is covered by a dense and complex network of cropmarks, including

examples of all the types discussed above. The complex nature of the

cropmarks indicates quite clearly that a multi-period landscape is

represented here, with many cropmarks crossing others with little

regard to alignment.

5.12 The barrow cemeteries

The earliest features are likely to be the ring-ditches. Three groups

are evident (Fig. 6 - A, B and C). A comprises one large ring-ditch

with at least four smaller examples scattered around it, one of which

clearly contains a central burial pit (Plate 2). The two northernmost

ring-ditches, and possibly the larger one, are cut by later linear

cropmarks suggesting that they had ceased to be visible when these

later field systems were laid out.

5.13 Group B also comprises one large ring-ditch flanked to the north

by at least ten smaller examples (Plate 1). Several pits are visible

within some of these ringditches. This group appears to be respected

by a rectilinear enclosure boundary, which encloses it on the north-east

and north-west sides before heading off to the

north-west. This may indicate that the enclosure was contemporary

with the cemetery (although if so, why not enclose the southern part

as well, or was this side limited by a stream channel now represented

by a wide sinuous cropmark?), or was laid out at a time when the cemetery

was no longer in use but still visible as a landscape feature (and

perhaps retaining some spiritual resonance as sacred ground).

5.14 Group C contains one possible ring-ditch, which is cut by (or

possibly cuts) the western arm of a rectilinear enclosure. The three

separate groups of ring-ditches indicate that some compartmentalisation

of the landscape was taking place. This is further suggested by reference

to Plate 2, where each group occupies a distinct

block of land bounded by sinuous cropmarks and largely amorphous areas

suggestive of geological features. These may well relate to former

stream channels.

5.15 Enclosures

The most striking cropmarks concern an extensive series of rectilinear

enclosures. At least two separate phases are visible from the photographs

(Plates 1-4) (although many more phases may actually exist, as not

all the features that respect, or appear to respect, each other are

necessarily contemporary), with a complex arrangement of regular rectilinear

enclosures of various sizes crossed by, or crossing over, a less regular

pattern of slightly curvilinear cropmarks. The regular

enclosures are best interpreted as field systems, probably evolving

over time with not all the visible elements of contemporary date.

Several smaller square features (Fig. 6 – D & E) are visible

within the overall pattern, possibly relating to small paddocks or

possibly even settlement foci (although there is no obvious sign of

internal features). Five lengths of trackway are visible, delineated

by parallel ditches (Fig. 6 - F-J). These represent droveways allowing

access to and between the various fields and other enclosures, and

were probably originally bounded by stock-proof hedges similar to

those that survive in the present landscape.

5.16 A curvilinear enclosure (Fig. 6 - K), now straddled by the parish

boundary, is noticeably different from the largely geometric pattern

within which it sits. Nevertheless, it seems to be part of the field

system, as it lies within the easterncorner of one large square field.

A large number of prominent discrete features are visible within it

(Plate 2), which may suggest the presence of pits. This feature may

be a possible settlement enclosure, with the pits representing storage

pits for grain, a common Iron Age practice.

5.17 Other features

The western side of the site is occupied by a large circular cropmark

(Fig. 6 - L). This feature superficially resembles a henge in shape,

and has often been interpreted as such. However, recent excavations

on similar sites have revealed that many of them are actually windmill

mounds. A similar interpretation is suggested for this example. This

suggestion is supported by photographic evidence. Plate 1 shows the

feature clearly positioned astride several linear cropmarks relating

to a rectilinear enclosure. The linears are not visible where they

would cross the feature, indicating that it is later in date (a henge

would normally be dateable to the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age,

while the rectilinear enclosures are probably of later prehistoric

date). In addition, the

feature is formed of a whitish ring of material, suggestive of a mound

that has been ploughed flat and the material spread about. The fact

that the mound material retains a distinctive colour suggests that

it is not of any great antiquity, as colour differentials would be

expected to disappear over time.

5.18 Finally, two areas of amorphous dark blotches (Fig. 6 - M and

N) visible on Plates 1-3 highlight areas of gravel quarrying, probably

of 18th-19th century date (Erith 1968).

6.0

WALKOVER SURVEY

6.1 A rapid walkover survey by the author was undertaken in respect

of the site on 11th October 2005. Conditions were good, being generally

dry, bright, and sunny.

6.2 The objective of the walkover survey was to identify historic

landscape features not plotted on existing maps, together with other

archaeological surface anomalies or artefact scatters, in order that

they may be described and added to the existing archaeological dataset

for the appraisal site.

Continued

on page 2