Metal detecting holidays in England with the World's most successful metal detecting club.20 years plus.

Twinned with Midwest Historical Research Society USA.

|

Where

do we detect -Early Colchester History

|

|

Celtic tribal map of Britain - red dot indicates our sites Camulodunum (Colchester) is a Romanisation of its Iron-Age name, the Fortress (dunum) of Camulos, God of War. The original site of the Iron-Age settlement Gosbecks was 3 miles southwest of the current city. This was a huge Iron-Age settlement covering a triangular area of approximately 10 miles. It was surrounded by rivers on two sides and an involved system of dykes on its open western end. These dykes are the only real vestiges of the settlement today with sunken lanes in the flat Essex countryside. Trinovantes and Catuvellauni (see above map, red dot)

This gave Caesar the excuse he was looking for to invade and after an unsuccessful attempt in 55 BC Caesar returned to finish the work in 54 BC. He chased Cassivellaunus back to his stronghold forcing Cassivellaunus to flee and come to terms.

Dubnovellaunus Late 1st BC to Early 1stC AD Full Celtic gold stater - Cunobelin 40AD - 1/4 Gold stater

Celtic stater of Addedomaros 37 - 33 BC The last Trinovantian king was called Addedomaros. His remains are possibly buried in the Lexden Tumulus close to Gosbecks. The king who was buried here had been ritually burned along with his goods that were a mixture of Celtic and Roman artefacts. Among them were the fragments of a small casket and inside was a medallion bearing the head of the Emperor Augustus.

Celtic gold 1/4 stater of the Cunoblein tribe 1stC BC to 40AD.(Biga type) Claudian invasion

Britain's first city

This is what the Roman fortress of Camulodunum was turned into. It became Britain's first-ever city. Doing this, the Romans quite literally brought civilisation to Britain, as the word derives from the Roman word civitas, meaning 'city'. The city of Colonia Victricensis (The City of Victory) was deliberately placed within the bounds of the Roman fortress, using its street plan and converting the barrack blocks into houses.

Similar monuments were erected in Rome, Gaul and at Aphrodisias in Turkey. Some fragments of these survive and because the Romans used the same formula for their monuments all over the empire, it is possible to use these to reconstruct pretty accurately what this arch and gate would have looked like. The inscription will have read: 'To Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, son of Drusus, Pontifex Maximus, with Tribunician Power for the eleventh time, Consul 5 times, hailed as Imperator 22 times, Censor, Father of his Country, the senate and people of Rome grant this because he received the surrender of 11 kings of the Britons conquered without loss, and he first brought the barbarian peoples across the Ocean under the authority of the Roman people'.

The local tribal elders were recruited into the temple cult but the financial burden of running the temple and the vicious maltreatment of the locals by the colonists was to be the route cause which boiled into the Boudiccan revolt.

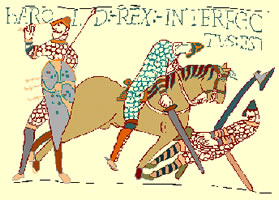

More info on Boudicca (Boadicea) (AD 62)

Devastation At the time of the revolt the Romans were so sure of their hold on East Anglia that there were only 200 members of the procurator's guard present .These and the local colonists were woefully inadequate to stop the tribal serge that descended upon an undefended Colchester. Tacitus says that: 'It seemed easy to destroy the settlement; for it had no walls. The Roman commanders had neglected to build walls and the archaeological record confirms that the walls of the legionary fortress had been filled in to make way for the temple precinct and other amenities.

Terror in the temple Archaeological evidence

No human remains linked to the Boudiccan Revolt have been recovered with the exception of one charred remains on North Hill. Did the townsfolk flee or were they taken elsewhere to be massacred ? The new city By AD 65 Colchester was surrounded by a newly built city wall. However by now the Roman administration took this opportunity to move the capital south to the better-placed Londinium (London) By AD 200 Colchester itself was now a fairly wealthy town. Its inhabitants could afford large well-appointed town houses whilst the wealthiest lived outside the towns in country villas. After the Romans

Both the sub-Roman Britons and the invading Anglo-Saxons were desperate to maintain some semblance of Roman civilisation. This is precisely what made the empire so attractive to the barbarians but they did not poccess the power or experience to make it work. Without the experience of the Roman imperial expertise in place to run the show Roman civilisation could not be maintained. This is what happened to Colchester where Anglo-Saxon settlers moved in and established grubenhauser style huts on the remnants of the Roman city almost immediately. At Lion Walk a fifth-century house was built directly on top of an abandoned Romano-British house soon after its abandonment. They even used the same street plan so that the High Street of modern Colchester still runs along the route of the Via Praetoria of the old Roman fort, with Head Street and North Hill forming a T-junction at one end along the line of the Via Principalis. As the new settlers became more sophisticated in their building techniques, they began to erect public buildings out of the rubble that was lying all around them. Colchester has several outstanding examples of this practice with the most significant of which is Holy Trinity Church. It was built during the eleventh century and is made entirely out of re-used Roman stone. Colchester Castle which was founded by William the Conqueror himself and again out of re-used Roman stone. This great monument to the last of Britain's conquerors was therefore placed directly on the spot where the first great monument to the conquest of Britain had been erected over 1,000 years before.

Later Colchester history,pictures and links

|

When

Claudius became Roman emperor in AD 41 he understood that in order to

survive he needed a triumph. He used the appeal of the British chieftain

Verica as his excuse for action. Verica was a king of the Atrebates

who had been driven out by Cunobelin's successor, Caratacus. The Roman

legions under Aulus Plautius landed at Richborough surprising the British

army at the River Medway and pushed Caratacus back to his stronghold

at Colchester.

When

Claudius became Roman emperor in AD 41 he understood that in order to

survive he needed a triumph. He used the appeal of the British chieftain

Verica as his excuse for action. Verica was a king of the Atrebates

who had been driven out by Cunobelin's successor, Caratacus. The Roman

legions under Aulus Plautius landed at Richborough surprising the British

army at the River Medway and pushed Caratacus back to his stronghold

at Colchester. Even

before it was complete the function of the fortress had been changed.

The conquest of Britain had moved on and instead of a military base

what Rome needed now was a colony. The Roman word colonia was a specific

term for a planned town inhabited by military veterans. They would be

allocated plots of land within the bounds of the settlement in order

to establish a Roman presence within the conquered area.

Even

before it was complete the function of the fortress had been changed.

The conquest of Britain had moved on and instead of a military base

what Rome needed now was a colony. The Roman word colonia was a specific

term for a planned town inhabited by military veterans. They would be

allocated plots of land within the bounds of the settlement in order

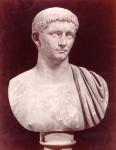

to establish a Roman presence within the conquered area.  The

annex of the old fortress was converted into the precinct for a monumental

Temple to the imperial cult. Today the site is occupied by a Norman

castle which was built directly onto the foundations of the old temple

out of Roman stone. Within the temple stood a life-size bronze statue

of the Emperor Claudius, of which the head still survives.

The

annex of the old fortress was converted into the precinct for a monumental

Temple to the imperial cult. Today the site is occupied by a Norman

castle which was built directly onto the foundations of the old temple

out of Roman stone. Within the temple stood a life-size bronze statue

of the Emperor Claudius, of which the head still survives.